Do languages die? Dr. Luzzi, son of Italian immigrants, reveals the answer.

Dr. Luzzi explains that languages and dialects can die when the next generation no longer speaks their parents’ native tongue. Luzzi also warns that without the language to describe the memories of our departed forebears, the memories themselves fade away.

Speaking to my father in a dead dialect.

|

|

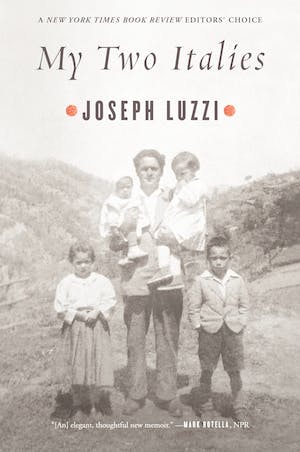

Joseph Luzzi holds a doctorate from Yale and teaches at Bard. He is the author of several books including My Two Italies, a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice. His essays and reviews have appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Bookforum, and the Times Literary Supplement. |

Writers throughout history reflected on what it means when a language evolves.

THE 18TH CENTURY Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico believed that as a civilization progressed, it lost touch with its creative origins. An ancient warrior would never declare “I’m angry”; he would wax metaphorical with “my blood boils.” The Roman poet Horace went a step further, believing that when words died they took memories with them. Just as forests change their leaves each year, so, too, do words: new languages “bloom and thrive” but only after “the old race dies.”

Growing up, the author - child of Italian immigrants from Calabria - witnessed his parents’ dialect languish in the United States of the 1950s.

Growing up, I could feel the language of my parents wither and die like autumn leaves. They had immigrated to the United States from Calabria in the late 1950s and continued to speak the dialect of their poor southern Italian region, but it was a tongue frozen in time by exile and filled with words that no longer existed in their homeland.

|

The author’s Italian immigrant father managed to buy himself a new car from the dealer, despite the language barrier.

AFTER A DECADE in America, my father decided to buy a fancy car. The Italian for a car is “una macchina,” and the Calabrian equivalent is “’na macchina.” But in the car-crazy suburbs of postwar America, an immigrant such as my father was bound to defer to his host nation. He went to the Chevy dealership and asked for “’nu carru.” The Calabrian “’nu” sounds like new, and “carro” means cart. But the dealership knew what he meant, and sold my father a maroon 1967 Chevy Impala. He bought it the year that I, his first American child, was born.

His father’s Calabrian dialect showed through when he got angry and the colorful expressions he used.

My father’s dialect flourished only in fits of anger: “mala nuova ti vo’ venire” (“may a new harm befall you”), when you annoyed him; “ti vo’ pigliare ’na shcuppettata” (“may you be shot”) and “ti vo’ brusciare l’erba” (“may the ground beneath you combust”) when you really got under his skin. It’s difficult to translate these makeshift phrases. Better just to imagine them uttered by a man who could pick up a small backyard shed.

His Italian immigrant mother made common English words her own by adding Calabrian sounds to them.

My mother faced her own herculean linguistic challenges. There were no freezers in her Italy, so when she wanted to preserve goods on ice, she talked about “frizzare,” to freeze, rather than the standard “congelare.” When her six children got the best of her, she threw her hands up and added an extra vowel to the ends of her Americanized words. We washed our clothes in a “uascinga mascina,” vacuumed the carpet with a “vachiuma cleena,” and drank lemonade on the “porciu” — the porch.

|

The author’s Italian immigrant parents Italian-ized their English, and the author took pride in his family’s Calabrian origin and identity in a new country.

MY PARENTS' skirmishes with standard Italian were nothing compared to the all-out war they waged on English. They would answer calls for their sons by saying “she’s a no’ home.” I took this gender-bending as an assertion of my individuality, my access to a world that separated me from all the other kids on the block. I may have lived in a three-bedroom ranch just like everyone else, but we were different. My family had no need to worship the idols of the second- and third-generation immigrants, with their cries of “mamma mia.” When my father swore at me in Italian, he did so out of anger and not nostalgia.

In true Italian fashion, his Italian immigrant parents kept a prolific garden, whose bounty included fruits for preserving, vegetables, tomatoes, grapes for wine, and prizewinning squash, which the local paper came to photograph.

This authenticity extended to the table. While my friends with grandparents from Sicily talked about Italian food, my parents produced it. Each year they churned out hundreds of jars of preserved peaches, pears and tomatoes; gallons of red wine; and bushels of cucumbers, peas and potatoes. Plus the showpiece crop, squash.

One year the local paper took a photo of my father and his prizewinning, five-foot-long gourds. Sensing he was on display, he stayed silent for the whole shoot. He didn’t understand how feeding your family could translate into a human-interest story. But make no mistake: he was proud to have created such a prodigious vegetable, and he made sure the part in his hair was just so when the picture was snapped. His face was wrinkled, and he had to lean on his cane when he reached for the prize gourd. He was only in his 60s but old age had been forced upon him prematurely by a massive stroke that paralyzed most of his left side.

Despite growing all the produce, the father only had Calabrian words to talk about growing food, unlike his children - all college educated and now culturally distant from their parents’ birthplace; he died in 1995, around the time of the garden photo shoot.

My father struggled to explain to the photographer how he grew his vegetables. He had only Calabrian words for the plants, procedures and tools. Each of his children had attained some form of higher education and, with it, freedom from the strife and poverty that had chased him from Italy. We now found his background primitive and remote. He had translated or “carried over” both a family and a dialect. After all this, he believed it was his right to talk about his squash on his own terms. Around the time of the photo, he poured a cement base for a picnic table near his garden. Before it dried, he signed it with a branch: P.L. Nato Acri 1923. Pasquale Luzzi, born in Acri, Italy, 1923. He died just months later, at the end of summer in 1995. In the obituary, my father’s passion for gardening was listed as his “hobby,” a word that didn’t exist in his Calabrian.

|

After his father’s death, the author struggled to find the right words in the right dialect to speak to his deceased father, whose voice he still heard. He felt that without the words he would lose the memories.

AFTER HIS DEATH, I would hear my father’s voice but didn’t know how to respond. When I imagined myself speaking to him in English, it sounded pedantic and prissy. Answering in Italian was no less stilted, either when I tried to revive my Calabrian or when I used the textbook grammar that was unnatural to both of us. I had so much to tell him but no way to say it, a reflection of our relationship during his lifetime. Without his words, I was losing a way to describe the world. Memories suddenly mattered more than ever before, and I didn’t know if I could find the language to keep them alive.

The author uses his parents’ dead dialect of Calabrian when he communes with his lost father, though he does so in silence.

Dante wrote in his treatise on language that though men and women must communicate with words, angels can talk to one another in silence. Speaking with someone who has died is similar. You learn early on that it is best to concentrate on the person you’ve lost with as little verbal clutter as possible. Perhaps this Calabrian I now speak with my father is the truly dead dialect, the language that neither changes nor translates.

A familiar memory of his Italian immigrant father tending his fig tree comes to the author’s mind, but, unless he holds onto the Calabrian words to describe the scene, the vision fades, and his mourning turns to memory.

When I think of him now, I see him digging in his garden, unearthing the ficuzza, Calabrian for his beloved fig tree, from its winter slumber and propping it up for the coming spring. But once I put a word to this picture, once this “ficuzza” becomes a “fico,” standard Italian for fig tree, he will have left me. This is when mourning becomes memory, and when it’s time to say goodbye to a language and a person I knew all too briefly.

Joseph Luzzi

Originally published in the NY Times. Reprinted with permission from the author.

|

My Two Italies: A Personal and Cultural History

Thursday, September 29th 2022 | 8:00 - 9:00PM EDT 📍Virtual Event |

.png)